For decades, only a Le Fort I could effectively treat a gummy smile (SG)! Since most patients are reluctant to undergo surgery (risks associated with the intervention, additional costs...), orthodontists have been limited to treating the associated issues, overlooking what was often the main reason for consultation. Failure was thus anticipated, regardless of the successes achieved otherwise.

The new possibilities brought by the tads have completely changed the game: the orthodontic imposition of an area or the entire maxillary arch has thus become a compelling alternative to the correction of the G.S., and in many cases superior to the surgical solution. These corrections are now among the most gratifying types of treatment for an orthodontist, since the transformation of the smile of these patients - both aesthetically and emotionally - is so important.

And so, it was only fitting that when I integrated tads into my daily practice nearly sixteen years ago, that one of my priorities was to design specific procedures for the different clinical forms of GS.

The concept I will be sharing in this case study is designed to manage the entire gummy smile (anterior and posterior). This procedure allows me to obtain, in a simple and non-invasive way, phenomenal facial and dental results. Associated therapies such as gingivoplasty (which depends on the clinical crown height and the situation of the attachment of the gums) and botulinum toxin (which allows to limit the ascension of the upper lip) have their own indications and can in no way replace the reduction of the dentoalveolar height.

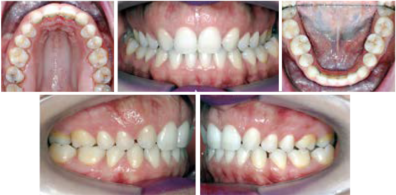

1. Smile before treatment.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CLINICAL CASE

Mrs. K, 31 years old, had the misfortune to undergo an iatrogenic orthodontic treatment during her teenage years (four years of braces). She had since resigned herself to living with this unsightly smile, all orthodontists consulted having assured her that nothing more could be done (Figs. 1 and 2).

The patient was diagnosed with 12-22 agenesis, and her orthodontist chose to extract 34-44 to "restore balance". The result, both dental and facial, was disastrous (Fig. 3): a transverse contraction of both arches, a posterior crossbite, a serious GS, and a concaved profile, which had an unfortunate psychological impact on this young woman's self-esteem.

So, when I told her that I had a non-surgical solution for her in a shorter period of time than expected, the patient discreetly wiped away a tear and smiled happily.

DIAGNOSIS

Most of these patients learn, over the years, to hide their gummy smile. It is therefore necessary to evoke a true authentic smile, different from the posed voluntary smile. During this spontaneous smile, the patient exposes a gingival height of 6 to 7 mm both anteriorly and posteriorly.

The measurement of the incisal exposure at rest is an equally important factor. This exposure should not exceed 2 to 3 mm or one-third of the total height of the central incisors. In this case, the resting exposure is 7 to 8 mm and will require an anterior and posterior ingression of about 5 mm.

With the patient's agreement, it was decided to perform an upper lip thickening - either during or at the end of the treatment. This adjuvant procedure will contribute to the correction of the gummy smile (Fig. 4).

2a-e. Intra-oral views before treatment.

3 and 4. Profile and smile of the patient pretreatment.

TREATMENT OBJECTIVES

The goals set for this treatment require some of the least predictable orthodontic procedures:

- Transverse expansion and enhancement of the overall arch form without generating spaces. This procedure will be the most time consuming of all;

- Ingression of the entire maxillary arch (anterior and posterior ingression) of about 4 to 5 mm;

- Advancement of the two arches to enhance the labial support and to reduce the concavity of the face profile; this is the most difficult procedure to perform. This difficulty will be solved by the particular sequence of shifts and by the planning of the treatment.

TREATMENT

The patient chose fixed braces. A standard crown torque was chosen on the central front incisors.

The canines and first pre-molars were both fitted with canine attachments and a high torque. This choice was based on three main considerations: the need to preserve the integrity of the vestibular cortex on these teeth; the need to compensate for the effects of the Class II and anterior vertical elastics that would be required; and the need for transverse expansion ( a negative torque on the canines and first bicuspids would have limited the transverse development of the posterior sectors) (Fig. 5a-c).

The tads are always placed early in the treatment, as early as the second appointment, generally between two and three weeks. In this particular case of agenesis and given the local anatomical conditions, they were placed between 1 and 2 (Fig. 6a,b).

One of the most frequently made mistakes is to wait for the arch wires to start the ingression. The torque and ingression of the maxillary incisors should be initiated on the Cu Ni (2 oz) leveling arches. They are continued on the steel arch wires (6 oz), with the steel arch wires enabling transverse control.

This can be achieved in two ways: by Nitinol coil, or by Gen 2 chains (Fig. 7a,b).

For evident aesthetic reasons, activation by chains was favored. This method also enables the applied forces to be light and intermittent.

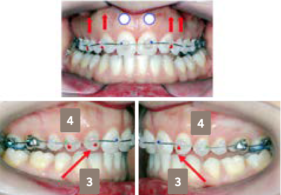

5a-c. Installation of the braces: positioning of the brackets and choice of torque.

6a,b. Installation of the tads between 1 and 3.

7a,b. Setting in charge.

8. Initialization of the anterior ingression on CuNi arc.

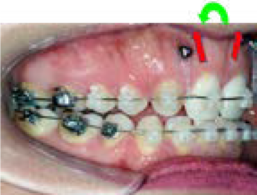

9. Five months later, an anterior infraclusion appeared. Installation of the posterior tads

and the beginning of the posterior ingression.

BIOMECHANICS AND SEQUENCE OF MOVEMENTS

Phase 1

Anterior ingression and advancement of the maxillary arch by counterclockwise rotation of the maxillary occlusal plane, creating an anterior gap and an increased incisal overhang (Fig. 8).

Phase 2

Beginning of posterior ingression with clockwise rotation of the maxillary occlusal plane. The maxillary posterior ingression contributes to closing the anterior overbite. The need for expansion has obviated the need to place tads on the palatal surface (Fig. 9).

Phase 3

Anterior and forward erosion of the entire mandibular arch, using class II intermaxillary elastics and anterior vertical elastics, while the maxillary arch ingression is stabilized (Fig. 10).

I have often been asked why the anterior and posterior ingressions were not performed simultaneously. It was crucial to proceed in this order. The posterior ingression initiated at the beginning would have counteracted the counterclockwise rotation of the maxillary occlusal plane and thus the advancement of the upper arch, which in the last phase was the driving force for the advancement of the mandibular arch (Figs. 11 to 13).

En achetant votre Viagra, Cialis, Levitra sur notre pharmacie a-pharma.fr en ligne, vous basculez automatiquement vers toute une batterie de privilèges et nous vous vous accompagnons tout au long de votre achat, grâce aux conseils et guides intégrés dans chaque produit.

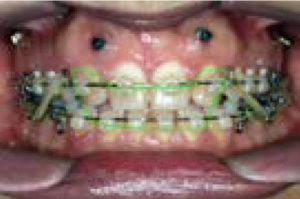

10. Egression and advancement of the lower arch with intermaxillary elastics on the maxillary arch supported by the anterior tads.

11. Intercuspidation.

12a,b. Smile at the end of the orthodontic treatment after eighteen months of work.

13a,b. An aesthetic optimization by 4 to 4 facets is planned. In the meantime, transitional composites have been made.

14a,b. Smile after treatment.

CONCLUSION

The ingression phase (anterior and posterior) lasted ten months. The expansion and transverse development required an additional six months. The total duration of the treatment was eighteen months.

The transformation of the smile is phenomenal. It is the result of both the impaction and the effects of the orthodontic mechanics of expansion and creation of a harmonious arch form and smile line. Self-ligating bracket mechanics and variable torques have certainly contributed to the efficiency of this treatment method (Fig. 14a,b). Well-executed veneers will undoubtedly enhance the patient's smile.

The orthodontist, more than ever before, is today the major actor of the face with an unprecedented therapeutic power. He or she must seize this opportunity and not succumb to the ease of treatment protocols decided by algorithms, and must constantly raise his or her level of practice.